Archive for the ‘Philosophy of The Numen’ Tag

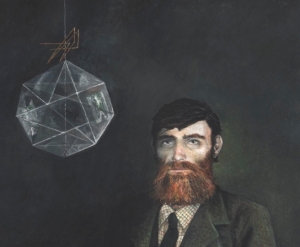

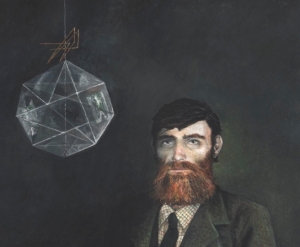

David Myatt

Three O’clock One English Morning

It is three o’clock one morning of an English Winter, and outside it is dark, and somewhat cold, with cloud to cover the stars of night and a slight breeze to rustle the fallen leaves that, somewhat dried by recent daytime snow-melting Sun, have been wind-gathered to rest where two parts of one garden fence meet and are met.

Inside, the soft candlelight that pleases as I sit, typing this, at my desk on which the decanter of fine vintage Port rests, still half-full, and music by Mozart gently suffuses the room, brought forth from grooves in vinyl by a modern marvel of sound reproduction. There is, alas, here in this modern dwelling no fire of logs to warm, as in that farmhouse, abode for many happy years until quite recently… Instead, only the warmth of such rememberings as often keep this old man happy in these, the twilight years of his, of my, life.

Much to recall; and much to remain silent about, untransmitted by words such as this – to be brought forth, and some of which have been brought forth, only aurally to trusted friends of long-standing who may or who may not, according to their own judgement, recount such matters for and to others, by whatever means, but only after I myself am dead. Thus, there are some things I will not comment about, here, by written means such as this.

So, to try and answer at least some of your questions, although trying to abridge four decades of experiences into one concise reply will of necessity mean some terse and perhaps unsatisfactory explanations.

In Respect of Adolf Hitler

As I wrote some years ago while living that Way of Life known as Al-Islam:

I have never, in my heart and mind, renounced my belief in Adolf Hitler as a good man, an honourable man, who – believing in God – strove to create a just and noble society, and who was destroyed by the ignoble machinations of those opposed to what is good and who have spread dishonourable lies about him, his followers and his Cause. Thus it is that I find I cannot denounce this noble man and those who fought and died for the cause he upheld, as I cannot and will not denounce those who today honourably (and I stress honourably) continue the struggle in his name and who respect the Way of Life which is Al-Islam… Thus it is that I continued for several years… with Reichsfolk – an honourable organization striving to presence something of the Numen I believe was manifest in National-Socialist Germany and in and through the life of Adolf Hitler.

Furthermore, the National-Socialism of Reichsfolk was the ethical, non-racist, National-Socialism I had developed in the late nineteen nineties; a Way of Life which saught to respect the difference and diversity of Nature, and which saught the development of separate, free, ethnic nations, with their own culture and identity, with these nations co-operating together, with no one race believing they were somehow superior to, or better than, any other race, but with each striving to achieve their differing Destinies, with there being no hatred of other races but instead a respect, deriving from honour.

This non-racist National-Socialism was developed for two main reasons. First, because I considered that the notion of racial superiority was untenable because it was fundamentally dishonourable; that is, unethical. Second, because I realized that the old type of National-Socialism led to unethical conflict, and that modern warfare was itself unethical.

In Respect of National-Socialism

For some thirty years, from the late nineteen sixties to the late nineteen nineties (CE), I actively strove by various means, political and otherwise, to propagate National-Socialism with the overt aim of creating, in my own homeland, another NS State, on lines similar to that of NS Germany. Indeed, one might with truth say that this singular aim was the main, the most important, aim of my life.

For the first ten or so of those years I naively and idealistically believed that this goal was attainable by conventional political means, given good leadership and a correct explanation of what I then understood National-Socialism to be – a noble cause, based on the values of honour, of loyalty to comrades, and duty to one’s folk. I never saw or even imagined myself as some leader; instead, and knowing the importance of leadership, I saught to find someone to whom I could pledge my loyalty and who, unlike me, possessed the charisma, the virtues, of a genuine revolutionary NS leader. Indeed, it was something of a friendly jest among certain members of Column 88 that I was “a Himmler in search of his Adolf Hitler”.

Never finding such a leader – but always, during those decades, hoping that such a person would emerge – I floundered about, doing the best I could to propagate NS politically; and also trying keep the spirit, the ethos, of NS alive, as Colin Jordan had done and did do, until his death, although in a much better way than I ever did. For I was often reckless and impatient, and perhaps too fanatical at times. Not to mention occasionally arrogant, disdainful as I was on such occasions of advice from people such as CJ – who, for instance, considered that my plan for recruiting and using ruffians (as with the short-lived NDFM) was not only foolhardy but not really in keeping with the ethos of NS.

After those first ten years, while much personal experience was gained, little if anything political had been achieved, and not only not by me. No one else, no other NS (or even nationalist) organization, had achieved anything significant either, despite much commitment and effort by hundreds of supporters. Indeed, what I termed The Magian System seemed to be stronger, more tyrannical.

Thus, for most of the next two decades I occupied myself with other tactics, other than overt political ones. Trying to use covert means, and seeking to explain, codify, refine, and possibly evolve National-Socialism itself. However, toward the end of these two decades I did briefly return to active, overt, politics – forming and leading the NSM, but more to try and continue the work begun by a loyal and dedicated comrade than because I had changed my view of myself as a leader. For I hoped, even then, that this new organization might attract someone of the right calibre to lead it. But neither these covert tactics, nor this new political organization, worked, leading me, over of period of many years, to certain conclusions, and among which conclusions are and were the following.

1) The first conclusion was that NS – or something based upon or evolved from it – could only ever become a significant political force if there arose a leader of sufficient nobility to lead a new movement. For such a leader would be the movement – just as Adolf Hitler was both the NSDAP and NS Germany. That is, political programmes, slogans, propaganda, activities, ideology, meetings, marches, were all fundamentally irrelevant – if there was no such leader to inspire, to lead, to give one’s loyalty to, and who embodied the essence of the NS ethos, just as Adolf Hitler embodied the essence of German National-Socialism. Without such a unifying, charismatic, figure, all movements, organizations, groups, whatever the initial idealism and enthusiasm of their members, descended, sooner or later into squabbling factions, just as dishonourable behaviour and lack of loyalty became rife. Even some limited electoral success, as the BNP and other European nationalist movements have shown, does not prevent this process, so that such organizations soon devolve to be at best minor political parties, perhaps with some political representation, but without any realistic hope of being elected to power, despite their constant rhetoric to the contrary. Thus they become a minor irritant to The System, but no real threat to it.

2) The second, perhaps more disturbing, conclusion was that we ourselves are a significant part of the problem. That it is not just a question of simply changing the political system, but of changing ourselves, as individuals, in a fundamental way.

Thus, and for example, perhaps a majority of those of European ethnic descent were no longer Aryan in nature. Instead, they de-evolved to become what I termed Homo Hubris, and it was this new sub-species of the genus Homo which has become the often willing and the easily manipulated hordes who had sided with the Magian and so defeated NS Germany. Not only that, but it was these new White hordes who kept the whole Magian System going, by their obedience to its ethos, and by their love of, and even now need for, the abstractions and materialism of The System.

In a personal way – through a practical striving for covert action over many years – I discovered just how difficult it is to find people (freedom fighters) ready and willing to do practical deeds and possibly sacrifice themselves “for the Cause”. Partly because this Cause – supposedly our shared Cause – did not live in them: they merely agreed (instinctively or consciously) with some aspects of its outward tenets. That is, it was more akin to some fleeting, easily discarded interest, or some passion which they could and often would forget when some other passion came along to enchant or ensnare them. For our Cause was not for them a Way of Life, a numinous and living faith, but rather just one type of politics among many.

Furthermore, while perhaps a few individuals might be inspired to action – or a few other individuals might do some deeds, elsewhere – such few actions, such few deeds, did not and never would affect The System in any significant way, and certainly would not break it, simply because a majority still supported it, actively or passively, and certainly did not support “us”, our Cause.

One therefore discovered for one’s self the truth of the truism that practical resistance to tyranny – to an occupying power – only works if one has support, significant support and sympathizers, from one’s own people, from those so occupied because they resent such occupation and its tyranny. The hard reality was that a majority of our people did not even feel they were living under some alien tyranny, and that a significant percentage even embraced the ideas and the ways of the occupiers and their collaborators (the hubriati) so much so for so many decades that The System had ceased to be something which “they” (some alien interlopers) imposed upon “us” but instead had become a hybrid system, partly “theirs” but also now “ours”, although always under the influence and ultimate control of “them” and of those who benefited from such a system, such as the hubriati. In a simplistic sense, “we” – our folk, or a majority of them – had been changed, from within; or been bred and educated by The State to accept and endorse, or at least be fairly passive parts of, The System.

One therefore began to consider working to undermine The System not from within, but from without – by aiding those freedom fighters who for various reasons also wanted the demise of the Magian and their own oppressive systems, and who thus not only desired to live in their own lands in their own way, but who also had a Cause that many were ready to die for.

Then, after about a decade or so of such experience it became obvious that even this approach was also not working, and would most probably also not ultimately succeed. (a) It was not working partly for similar reasons it has not worked for “us” (although our efforts were on a far smaller scale, over less periods of time) – that is, because these external allies were also a minority among their own kind, with many many others of their kind actively supporting and even collaborating with “the enemy”, and even desiring to manufacture a type of Magian system in their own lands. Thus, they were as lost to their kind, as a majority of our people were lost to their own innate ethos and the potential latent within us. (b) It would probably not ultimately succeed because to do so it needed internal dissent in the heartlands of the West, which was not forthcoming. Indeed, while some dissent existed, it was an annoyance to The System rather than a threat, with perhaps a majority believing the propaganda levelled at those freedom fighters, and actively or passively supporting the policies of their governments aimed at disrupting and destroying those freedom fighters in other lands.

3) The third conclusion was that each and every European homeland was no longer European by ethnicity, given the large-scale and continuing immigration of many decades, and that – short of implausible practical civil wars and a significant change in exterior lands – there was no practical way to make them wholly European again, and thus build a new folkish State. Implausible, because as mentioned above, a majority of even each and every European folk would find such a practical, civil war, solution unacceptable now and in the foreseeable future; and because one small homeland alone could not take such steps to expel whole communities while Magian power and the Magian ethos held sway in other lands, for the lone small homeland would soon find itself subject to punitive sanctions and, ultimately, invasion and thence “regime-change”.

4) The fourth conclusion was that, in essence, The State itself – as concept, as idea, as ideal – was ultimately incompatible with the numinous essence behind what Adolf Hitler had intuitively presenced, manifested, as National-Socialism in Germany. That is, that The State could no longer be made numinous, or manifest the numen, as it had begun to do in NS Germany, and that NS Germany was only an intimation, a beginning, a pointer toward a deeper truth; a truth revealed in part by the defeat of NS Germany by the White Hordes incited and led-on by the Magian.

This is the truth of our natural and necessary tribal nature, and of the nature of honour itself. The truth of Numinous Law (the law of personal honour) and the truth of how the clan, with a living, numinous, tradition, is and always will be immune to the Magian, and the dishonourable, un-numinous, abstractions that the Magian and their hubriati have manufactured, and which abstractions stifle our potential, disconnect us from the numen, and profane and undermine Nature and thus the living folk communities which are and which have been natural manifestations of Nature.

5) My fifth, last, later, and possibly most significant if contentious, conclusion was that the very notion – the idea – of there existing, or of desiring to move toward the ideal of, some pure race was an abstraction, and as such was un-numinous and thus unethical; contrary to honour itself, and which honour I had concluded was a practical expression of the essence of personal empathy. That is, that both race itself and the concept of an ethnic folk were – just like the concepts of the nation and The State – causal, immoral, abstractions; and that what was needed were new clans, new tribes, not based on any abstractions, any ideology.

In Respect of the Future

Given these conclusions – arising from four decades of practical experience and from much reflexion – it is my view that the future lies in numinously pursuing two things. First, the numinous goal of new clans and tribes, and which new clans and tribes could be either (1) evolutionary manifestations of (derived from) the natural already existing folks found in and evolved by Nature (and which thus possess ancestral living traditions), or (2) honourably and thus ethically, entirely new folks (not based upon any particular ethnicity nor upon any belief in such ethnicity) and which new folks we ourselves found and establish by dwelling in a certain local area, and which begin as our own extended family, or that of ours and also of a few trusted friends who feel as we do. Second, in changing ourselves as individuals, within, by a striving to live in balance, in rural harmony, with Nature and by a striving to uphold the most important because numinous principle of personal honour.

There is thus, in either of these two possible ways, no involvement with practical politics, nor any desire to seek revolutionary change, by whatever means or tactics. In truth, there is no ideology, and no politics at all – only a living of life in a certain way. A rejection of The System by withdrawing from it, and letting it decay and fall as it is destined to decay and fall, as all such causal un-numinous systems decay and fall, given time.

The former – that is, (1) above, the first possible way – is, for example, the old way of Reichsfolk, and of kindred groups; and the latter – (2) above, the second possible way – is the ethical, human, way proposed by my own Philosophy of The Numen where what matters is a personal compassion, personal empathy, and personal honour. And it is the latter – the compassionate way of The Philosophy of The Numen – that represents my views, now; views, perspectives, obtained by the pathei-mathos of my past forty years. My experiences, my reflexion upon those experiences, have therefore changed me, as a person, and taken me far beyond, far away from, National-Socialism and even from what I termed, over a decade ago, the ethical NS of Reichsfolk.

In The Philosophy of The Numen, there is a return to a more human personal scale of things; to slowly growing, through the generations, the foundations for new communities. An evolution toward a new type of human being, a new human species, and a new type of culture. For these, we do not need some revolution, some ephemeral State, some ephemeral political type of power; some ephemeral military force. Instead, we only need to presence, to manifest, within us the numinous itself, beyond ever changing causal abstractions.

There is thus the perspective of decades, of centuries – born as this perspective of ours is from the wisdom of our experience; from a concentration on the important and the numinous as against the unimportant and the profane.

In Conclusion

Now, the decanter only a quarter full, and Dawn not long in duration away, it is time for a full English breakfast to ready me for the tasks of another daylight day, again.

But before then, perhaps I should, and in conclusion, quote some words of mine, recently written, which at least for me seem to capture the essence of my life and the understanding I believe I have garnished from such strange livings as have been mine:

What, therefore, shall I personally miss the most as my own mortal life now moves toward its fated ending? It is the rural England that I love, where I feel most at home, where I know I belong, and where I have lived and worked for many many years of my adult life – the rural England of small villages, hamlets, and farms, far from cities and main roads, that still (but only just) exists today in parts of Shropshire, Herefordshire, Yorkshire, Somerset and elsewhere. The rural England of small fields, hedgerows, trees of Oak, where – over centuries – a certain natural balance has been achieved such that Nature still lives and thrives there where human beings can still feel, know, the natural rhythm of life through the seasons, and where they are connected to the land, the landscape, because they have dwelt, lived, worked there year after year, season after season, and thus know in a personal, direct, way every field, every hedge, every tree, every pond, every stream, around them within a day of walking.

This is the rural England where change is slow, and often or mostly undesired and where a certain old, more traditional, attitude to life and living still exists, and which attitude is one of preferring the direct slow experience of what is around, what is natural, what is of Nature, to the artificial modern world of cities and towns and fast transportation and vapid so-called “entertainment” of others.

That is what I shall miss the most, what I love and have treasured – beyond women loved, progeny sown, true friends known:

The joy of slowly walking in fields tended with care through the hard work of hands; the joy of hearing again the first Cuckoo of Spring; of seeing the Swallows return to nest, there where they have nested for so many years. The joy of sitting in some idle moment in warm Sun of an late English Spring or Summer to watch the life on, around, within, a pond, hearing thus the songful, calling birds in hedge, bush, tree, the sounds of flies and bees as they dart and fly around.

The joy of walking through meadow fields in late Spring when wild flowers in their profusion mingle with the variety of grasses that time over many decades have sown, changed, grown. The joy of hearing the Skylark rising and singing again as the cold often bleak darkness of Winter has given way at last to Spring.

The simple delight of – having toiled hours on foot through deep snow and a colding wind – of sitting before a warm fire of wood in that place called home where one’s love has waited to greet one with a kiss.

The joy of seeing the first wild Primrose emerge in early Spring, and waiting, watching, for the Hawthorn buds to burst and bloom. The soft smell of scented blossoms from that old Cherry tree. The sound of hearing the bells of the local village Church, calling the believers to their Sunday duty. The simple pleasure of sitting after a week of work with a loved one in the warm Summer quietness of the garden of an English Inn, feeling rather sleepy having just imbued a pint or two of ale as liquid lunch.

The smell of fresh rain on newly ploughed earth, bringing life to seeds, crops, newly sown. The mist of an early Autumn morning rising slowly over field and hedge while Sun begins to warm the still chilly air. The very feel of the fine tilth one has made by rotaring the ground ready for planting in the Spring, knowing that soon will come the warmth of Sun, the life of rain, to give profuse living to what shall be grown – and knowing, feeling, that such growth, such fecundity, is but a gift, to be treasured not profaned…

These are the joys, some of the very simple, the very English, things I treasure; that I have loved the most, and whose memories I shall seek to keep flowing within me as my own life slowly ebbs away…

David Myatt

(Extracts from a letter to a friendly enquirer)

The Numinous Foundations of Human Culture

In your recently published autobiography, Myngath, you wrote that, and I quote – “a shared, a loyal, love between two people is the most beautiful, the most numinous, the most valuable thing of all.” Is that how you now feel about life?

Certainly. I have now reached the age when there seems to be a natural tendency to reflect on the past – to recall to one’s consciousness happy, treasured, moments from decades past, bringing as such recollections seem to do some understanding of what is important, precious, about life, about our mortal human existence.

One remembers – for instance – those tender moments of one’s child growing in the first years of their life – the moment of first walking, the first words, the time they feel asleep in your arms on that day when warm Sun and their joyful discovery of sand and sea finally wore them out… Or the tender moments of a love, shared, with another human being; perhaps evoked again by some scent (of a flower, perhaps) or by those not quite dreaming-moments before one falls asleep at night, or, as sometimes occurs with people of my age, in the afternoon after lunch or following that extra glass of wine to which we treat ourselves.

It is as if – and if we allow ourselves – we become almost as children again, but with the memories, the ability, to appreciate the time, the effort, the love, the tenderness, and often the sacrifice, that our own parents showed and gave to us but which we never really appreciated then in those moments of their giving. As if we wish we could be back there, then, with this our ageful understanding – back there, full of youth and unhampered by the ageing body which now seems to so constrain us. Thus, are we as if that, this, is all we are or have to give: this, our understanding, our now poignant understanding; this – perhaps a smile, a gesture, a look, a word, or those tears we might cry, silently, softy, when we are alone, remembering. Tears of both sadness and of joy; of memories and of hopes. Hopes that someone, somewhere, at some time, might by our remembering be infused, if only a little, with that purity of life which such ageing recollections seem to so exquisitely capture.

That purity which becomes so expressed, so manifest, if one watches – for example – a young loving mother cradling her baby. Look at her eyes, her face, the way she holds her hands. There is such a gentle love there; such a gentle love that artists should really try and capture again and again in music, in painting, in moving images, in words, in sculpture. And capture again and again so that their Art reminds us of that so very human quality, that so very fragile quality, which enables us – each, another separate human being – to be so gently aware of another person, and thus able for ourselves, if only for an instant, to feel that gentleness, that tenderness, in another. This tenderness, this love, should be captured and expressed again and again because such love is one of the foundations of human culture, and something we so often, especially we men, are so prone to forget when we allow ourselves to become subsumed with some abstraction, some idealistic notion of duty, or some personal often selfish emotion.

Thus are we reminded of the value, the importance, of human love, and the need for us to be empathic beings – to have and to develope our empathy so that we can shed our selfish self and the illusion of our separateness.

That sounds very much like some old hippy talking – preaching love and gentleness. But don’t you still uphold honour and surely that itself might sometimes require the use of force, of violence? Surely there is a contradiction, here – between such tenderness, such love, and such force?

Personally, I think there is no contradiction, only a natural human balance. One prefers love, gentleness, empathy, but one is prepared, if necessary, to defend one’s self and one’s loved ones from those who might act in a selfish, dishonourable, harmful, violent, way toward us in some personal situation.

This nature balance – an innate nobility – is possessed by many human beings, and has been, for millennia; which is why some people just naturally have a sense of fair-play and would instinctively “do the right thing” in some situations, for example if they saw two men (or even one man) battering a women in a public place or if they came across a group of yobs taunting an elderly disabled man. And it is this natural balance, this notion of fairness, which is another of the numinous foundations of human culture.

Thus, it is that, according to my understanding, it is personal love – with all its tenderness – combined with fairness, a sense of personal honour, and with the ability to empathize with other human beings, that are not only numinous, but which also express our culture, our social nature, and are the things we should value, treasure, and seek to develope within ourselves.

It is unfortunate, therefore, that our predilection for manufacturing and believing in abstractions has, over millennia, and especially in the past hundred or more years, detracted from these three noble virtues of personal love, personal honour, and empathy, and instead led to the manufacture of new types of living where some abstraction or other is the goal, rather than such virtues.

My own life – until quite recently – is an example of how a person can foolishly and unethically place abstractions before such virtues and thus cause suffering in others, and for themselves.

One reviewer of your autobiography wrote of it as a modern allegory; a story of personal redemption, but without God. Would you agree?

With my four-decade long love of abstractions I certainly seem to have been a good example of human stupidity and arrogance; of someone obsessed with ideas, and ideals, for whom love and personal happiness came second, at best. Someone who arrogantly, sometimes even fanatically, believed they were “doing the right thing” and who found or who made excuses for the suffering, both personal and impersonal, that he caused.

Even worse, perhaps, was that there were many times in my life when I understood this, instinctively, emotionally, and consciously, but I always ended up ignoring such understanding – at least until recently. So, in effect, that makes me a worse offender than many others.

So, yes – perhaps my life is one such allegory; one story of how a human being can return to the foundations of human culture, and thus embrace the numinous virtue of compassion, of ceasing to intentionally cause suffering, of considering that a shared and loyal love between two human beings is the most beautiful, the most precious, the most numinous, thing of all.

But without a religious dimension? That, surely, is the key here, and what makes your story so very interesting?

Certainly, a kind of redemption without a belief in conventional religion. But that is only my own personal conclusion, my own personal Way, which therefore does not necessarily mean it is correct. It is only my own Numinous Way, deriving from my own pathei-mathos, founded on empathy, compassion, honour, and where there is no need for some supreme deity, or some theology, or even for some belief in something supra-personal. Instead, I feel there is a human dimension here – a natural return to valuing human beings, born of empathy. That is, that what is important is a close, a personal and empathic, interaction between human beings, and a living in a compassionate and honourable way – rather than a religious approach, with prayer, with rituals, with notions of sin, of redemption by some some supra-personal deity, or some belief in some after-life and which after-life is ours if we behave in the particular ways that some religion or some Sage or teacher or prophet prescribes or describes.

Without, in particular, any texts or impersonal guidance or revelation – since we have all the guidance we need, or can have all the guidance we need, because of and with and through empathy; by means of developing empathy, and so feeling as others feel. Thus, we lose that egocentric – that selfish, self-contained – view of ourselves, and instead view, and importantly feel, ourselves as connected to, part of, other human life, other beings; we know, we feel, we understand, that they are us and that we are them, and that it is only the illusion of the self, the abstraction of the self, that keeps us from this knowing, this feeling, this understanding of ourselves as a nexion to all other Life.

Thus, there is – or seems to me to be – a natural simplicity here in this Way of Empathy, Compassion, and Honour: a child learning and maturing, to perchance develope into another type of human being who might perchance with others develope new, more loving, more empathic, more balanced, ways of social living, and thus a new type or species of human culture where abstractions no longer hold people in thrall.

Is this – in enabling this new culture – where you think artists have an important rôle to play?

Yes, artists and artisans as pioneers of a new type of human culture – artists and artisans of the Numinous who can presence, and thus express, in their works those things which can inspire us to be human, to be more human, and to value the numinous virtues of empathy, compassion, personal love, and personal honour.

David Myatt

2010 CE

Source – http://davidmyatt.wordpress.com/numinous-foundations-of-human-culture/

See also – Myatt: The Culture of Arete

The Balance of Physis – Notes on λόγος and ἀληθέα in Heraclitus

Part One – Fragment 112

σωφρονεῖν ἀρετὴ μεγίστη, καὶ σοφίη ἀληθέα λέγειν καὶ ποιεῖν κατὰ φύσιν ἐπαίοντας. [1]

This fragment is interesting because it contains what some regard as the philosophically important words σωφρονεῖν, ἀληθέα, φύσις and λόγος.

The fragment suggests that what is most excellent [ ἀρετὴ ] is thoughtful reasoning [σωφρονεῖν] – and such reasoning is both (1) to express (reveal) meaning and (2) that which is in accord with, or in sympathy with, φύσις – with our nature and the nature of Being itself.

Or, we might, perhaps more aptly, write – such reasoning is both an expressing of inner meaning (essence), and expresses our own, true, nature (as thinking beings) and the balance, the nature, of Being itself.

λέγειν [λόγος] here does not suggest what we now commonly understand by the term “word”. Rather, it suggests both a naming (denoting), and a telling – not a telling as in some abstract explanation or theory, but as in a simple describing, or recounting, of what has been so denoted or so named. Which is why, in fragment 39, Heraclitus writes:

ἐν Πριήνηι Βίας ἐγένετο ὁ Τευτάμεω, οὗ πλείων λόγος ἢ τῶν ἄλλων [2]

and why, in respect of λέγειν, Hesiod [see below under ἀληθέα] wrote:

ἴδμεν ψεύδεα πολλὰ λέγειν ἐτύμοισιν ὁμοῖα,

ἴδμεν δ᾽, εὖτ᾽ ἐθέλωμεν, ἀληθέα γηρύσασθαι [3]

φύσις here suggests the Homeric [4] usage of nature, or character, as in Herodotus (2.5.2):

Αἰγύπτου γὰρ φύσις ἐστὶ τῆς χώρης τοιήδε

but also suggests Φύσις (Physis) – as in fragment 123; the natural nature of all beings, beyond their outer appearance.

ἀληθέα – commonly translated as truth – here suggests (as often elsewhere) an exposure of essence, of the reality, the meaning, which lies behind the outer (false) appearance that covers or may conceal that reality or meaning, as in Hesiod (Theog, 27-28):

ἴδμεν ψεύδεα πολλὰ λέγειν ἐτύμοισιν ὁμοῖα,

ἴδμεν δ᾽, εὖτ᾽ ἐθέλωμεν, ἀληθέα γηρύσασθαι [3]

σωφρονεῖν here suggests balanced (or thoughtful, measured) reasoning – but not according to some abstract theory, but instead a reasoning, a natural way or manner of reasoning, in natural balance with ourselves, with our nature as thinking beings.

Most importantly, perhaps, it is this σωφρονεῖν which can incline us toward not committing ὕβρις (hubris; insolence), which ὕβρις is a going beyond the natural limits, and which thus upsets the natural balance, as, for instance, mentioned by Sophocles:

ὕβρις φυτεύει τύραννον:

ὕβρις, εἰ πολλῶν ὑπερπλησθῇ μάταν,

ἃ μὴ ‘πίκαιρα μηδὲ συμφέροντα,

ἀκρότατον εἰσαναβᾶσ᾽

αἶπος ἀπότομον ὤρουσεν εἰς ἀνάγκαν,

ἔνθ᾽ οὐ ποδὶ χρησίμῳ

χρῆται [5]

It therefore not surprising that Heraclitus considers, as expressed in fragment 112, the best person – the person with the most excellent character (that is, ἀρετὴ) – is the person who, understanding and appreciating their own true nature as a thinking being (someone who can give names to – who can denote – beings, and express or recount that denoting to others), also understands the balance of Being, the true nature of beings [cf. fragment 1 – κατὰ φύσιν διαιρέων ἕκαστον], and who thus seeks to avoid committing the error of hubris, but who can not only also forget this understanding, and cease to remember such reasoning:

τοῦ δὲ λόγου τοῦδ᾽ ἐόντος ἀεὶ ἀξύνετοι γίνονται ἄνθρωποι καὶ πρόσθεν ἢ ἀκοῦσαι καὶ ἀκούσαντες τὸ πρῶτον [6]

but who can also deliberately, or otherwise, conceal what lies behind the names (the outer appearance) we give to beings, to “things”.

DW Myatt

2455369.713

Notes:

[1] Fragmentum B 112 – Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, ed. H. Diels, Berlin 1903

[2] ” In Priene was born someone named and recalled as most worthy – Bias, that son of Teuta.”

[3]

We have many ways to conceal – to name – certain things

And the skill when we wish to expose their meaning

[4] Odyssey, Book 10, vv. 302-3

[5] “ Insolence plants the tyrant. There is insolence if by a great foolishness there is a useless over-filling which goes beyond the proper limits. It is an ascending to the steepest and utmost heights and then that hurtling toward that Destiny where the useful foot has no use…” (Oedipus Tyrannus, vv.872ff)

[6] ” Although this naming and expression, which I explain, exists – human beings tend to ignore it, both before and after they have become aware of it.” (Fragment 1)

^^^

Above text in pdf format:

heraclitus-112.pdf

Article Source: http://thenuminousway.wordpress.com/heraclitus-fragment-112/

Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ

Physis, Nature, Concealment, and Natural Change

The phrase Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ – attributed to Heraclitus [See Note 1] – is often translated along the following lines: Nature loves to conceal Herself (or, Nature loves to hide).

Such a translation is somewhat inaccurate, for several reasons.

First, as used here, by Heraclitus, the meaning of Φύσις is rather different from his other usage of the term, as such usage is known to us in other fragments of his writings. For the sense here is of Φύσις rather than φύσις – a subtle distinction that is often overlooked; that is, what is implied is that which is the origin behind the other senses, or usages, of the term φύσις.

Thus, Φύσις (Physis) is not simply what we understand as Nature; rather, Nature is one way in which Φύσις is manifest, presenced, to us: to we human beings who possess the faculty of consciousness and of reflexion (Thought). That is, what we term Nature [See Note 2] has the being, the attribute, of Physis.

As generally used – for example, by Homer – φύσις suggests the character, or nature, of a thing, especially a human being; a sense well-kept in English, where Nature and nature can mean two different things (hence one reason to capitalize Nature). Thus, we might write that Nature has the nature of Physis.

Second, κρύπτεσθαι does not suggest a simple concealment, some intent to conceal – as if Nature was some conscious (or anthropomorphic) thing with the ability to conceal Herself. Instead, κρύπτεσθαι implies a natural tendency to, the innate quality of, being – and of becoming – concealed or un-revealed.

Thus – and in reference to fragments 1 and 112 – we can understand that κρύπτεσθαι suggests that φύσις has a natural tendency (the nature, the character) of being and of becoming un-revealed to us, even when it has already been revealed, or dis-covered.

How is or can Φύσις (Physis) be uncovered? Through λόγος (cf. fragments 1, and 112).

Here, however, logos is more than some idealized (or moralistic) truth [ ἀληθέα ] and more than is implied by our term word. Rather, logos is the activity, the seeking, of the essence – the nature, the character – of things [ ἀληθέα akin to Heidegger’s revealing] which essence also has a tendency to become covered by words, and an abstract (false) truth [ an abstraction; εἶδος and ἰδέα ] which is projected by us onto things, onto beings and Being.

Thus, and importantly, λόγος – understood and applied correctly – can uncover (reveal) Φύσις and yet also – misunderstood and used incorrectly – serve to, or be the genesis of the, concealment of Φύσις. The correct logos – or a correct logos – is the ontology of Being, and the λόγος that is logical reasoning is an essential part of, a necessary foundation of, this ontology of Being, this seeking by φίλος, a friend, of σοφόν. Hence, and correctly, a philosopher is a friend of σοφόν who seeks, through λόγος, to uncover – to understand – Being and beings, and who thus suggests or proposes an ontology of Being.

Essentially, the nature of Physis is to be concealed, or hidden (something of a mystery) even though Physis becomes revealed, or can become revealed, by means such as λόγος. There is, thus, a natural change, a natural unfolding – of which Nature is one manifestation – so that one might suggest that Physis itself is this process [ the type of being] of a natural unfolding which can be revealed and which can also be, or sometimes remain, concealed.

Third, φιλεῖ [ φίλος ] here does not suggest “loves” – nor even a desire to – but rather suggests friend, companion, as in Homeric usage.

In conclusion, therefore, it is possible to suggest more accurate translations of the phrase Φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ. All of which correctly leave Φύσις untranslated (as Physis with a capital P), since Φύσις is the source of certain beings [or, to be precise, Physis is the source of, the being behind, our apprehension of certain beings] of which being Nature is one, and of which our own, individual, character, as a particular human being, is another.

One translation is: Concealment accompanies Physis. Or: Concealment remains with Physis, like a friend. Another is: The natural companion of Physis is concealment.

Or, more poetically perhaps, but much less literally, one might suggest: Physis naturally seeks to remain something of a mystery.

DW Myatt

2455357.951

Notes:

[1] Fragmentum B 123 – Fragmente der Vorsokratiker ed. H. Diels, Berlin 1903. An older reference for the text, still sometimes used, is Fragment 10 [Epigrammaticus] (cf. GTW Patrick, after Bywater; et al). If the first letter of φύσις is not capitalized, then the phrase is φύσις κρύπτεσθαι φιλεῖ

Heraclitus flourished c. 545 – 475 BCE.

[2] Nature can be said to be both a type of being, and that innate, creative, force (that is, ψυχή) which animates physical matter and makes it living.

^^^

Article source: http://thenuminousway.wordpress.com/heraclitus-fragment-123/

Editorial note – In my view, the following philosophical article by Myatt is one of his most important works.

Written in May of this year, 2010 CE, it succinctly and clearly outlines the philosophical basis for Myatt’s own philosophy, called The Numinous Way, also now known as The Philosophy of The Numen.

In this essay, Myatt explains the philosophical nature of empathy – the basis of his ethics – and of his concept of acausality. Further details of the philosophical nature of acausality are given, by Myatt, in his essay The Ontology of Being.

David Myatt, from a painting by Richard Moult

Acausality, Phainómenon, and The Appearance of Causality

Phainómenon and Causality

What is apparent to us by means of our physical senses – Phainómenon – is that which is grounded in causality. That is, the phenomena which we perceive, is, or rather hitherto has been, perceived almost exclusively in terms of causal Space and causal Time. To understand why this is so, let us consider how we have regarded Phainómenon.

We assign causal motion or movement to the phenomena which we perceive, as we assign other properties and qualities we have posited, such as colour, smell, texture, physical appearance, and, most importantly, being. Hence, we come to distinguish one being from another, and to associate certain beings with certain qualities or attributes which we have assigned to them based on observation of such beings or on deductions and analogies concerning what are assumed to be similar beings.

This process – and its extension by observational science – has led us to distinguish or perceive individual human beings (ourselves, and the others); distinguish a human being from a tree and from, for example, a cloud, a rock, and a cat. It has led us to assign a specific tree to a certain type of tree, so that “that tree, there” is said to be an Oak tree, to belong to a class of similar things which are said to have the same or similar qualities and properties, and which properties or qualities can include such things as texture or colour or shape. It has also led us to make a distinction between a living being (an organism) and inert matter, with a living being said to exhibit five particular properties or qualities: a living being respires; it moves (without any external force acting upon it); it grows (changes its outward form without any outside force being applied); it excretes waste; it is sensitive to, or aware of, its environment; it can reproduce itself, and it can nourish itself.

Thus, we have assigned a type of being (the property of having existence) to what we have named rock; a type of being to what we have named clouds; a type of being to ourselves; and types of being to trees and cats. This assignment derives from our perception of causality – or rather, from our projection of the abstraction of causality upon Phainómenon. For we have perceived being in terms of physical separation, distance between separate objects (that is, in terms of a causal metric); in terms of the movement of such perceived separate objects (and which movement between or separation of objects existing in causal Space, can and has served as one criteria for distinguishing types of being); and in terms of qualities or properties which we have abstracted from our physical perception of these beings, be these qualities or properties direct ones (deriving for example, from sight, smell, texture, taste) or indirect, deduced, theorized, or extrapolated ones, such as, for example, the property of gases, the property of liquids, of solids, and such things as atoms and molecules.

In general, therefore, all such things (all matter and beings) are said to exhibit the property of existing, of having being, in both (causal) Space and at a certain moment or moments of (causal) Time. That is, being and beings have hitherto been understood in terms of, defined in terms of, causality, so that being itself has been assigned a causal nature. Or, expressed another way, it is said that causal Time and a causal, physical, metrical, separation (causal Space) are the ground, or the horizon, of Being.

Knowledge and Acausal Being

While this particular causal understanding of being and of beings has proved very useful and interesting – giving rise, for example, to experimental science and certain philosophical speculations about existence – it is nevertheless quite limited.

It is limited in three ways. First, because both causal Space and causal Time are human manufactured abstractions imposed upon or projected by us upon Phainómenon; second, because such causality cannot explain the true nature of living beings; and third, because the imposition of such causal abstractions upon living beings – and especially upon ourselves – has had unfortunate consequences.

The nature of all life leads us to conceive of non-causal being. That is, that life – that living beings – possess acausality; that their being is not limited to, nor can be described or defined by, a causal Space and a causal Time. Or expressed another way, the being of all living beings exists, has being in, acausal Space and acausal Time, as well as in our phenomenal causal Space and causal Time.

How, then, can we know or come to know, this acausal being, given how causal being has been and is known to us in observable phenomena? And just how and why does the nature of all life leads us to conceive of non-causal being?

We are led to the assumption or the axiom of acausality because we possess the (currently underused and undeveloped) faculty of empathy [ συν-πάθοs ] – that is, the ability of sympathy, συμπάθεια, with other living beings. It is empathy which enables us to perceive beyond (to know beyond) the causal – and particularly and most importantly beyond the causal abstraction of the separation of beings: beyond the causal separateness, the self-contained individual being that causal apprehension presents to us, or rather has hitherto presented to us. That is, empathy reveals the knowing of ourselves as nexions – as a connexion to other life by virtue of the nature, the being, of life itself, and which life we, of course, as living beings, possess.

This empathy is in addition to our other faculties, and thus compliments and extends the Aristotelian essentials relating to Phainómenon [1]. Furthermore, it is by means of empathy – by the development of empathy – that we can begin to acquire a limited understanding and knowledge of acausality. Thus, this knowledge of acausality extends the type of knowing based upon or deriving from a causal understanding of Phainómenon.

Hence, for living beings, causality (and its separateness) is appearance, rather than an expression of the nature of the being that living beings possess.

The Being of Life

Acausal being is what animates inert physical matter, in the realm of causal phenomena, and makes it alive – that is, possessed of life, possessed of an acausal nature. Or, expressed another way, living beings exist – have their being – in both acausal Space and acausal Time, and also in causal Space and in causal Time. That is, they are nexions between the acausal continuum (the realm of acausal Space and acausal Time) and the causal continuum (the realm of causal Space and causal Time; the realm of causal phenomena).

Thus, living beings, in the causal, possess a particular quality that other beings do not possess – and this quality cannot be manufactured, by us (in the causal, and by means of causal science and technology), and then added to inert matter to make that matter alive. That is, we human beings cannot abstract this quality – this acausality – out from anything causal, and then impose it upon, or add it to, or project it upon, some causal thing to make that thing a living being.

Furthermore, the very nature of acausal being means that all life is connected, beyond the causal, and this due to the simultaneity that is implicit in acausal Time and acausal Space. For we may conceive of the acausal as this very matrix of living connexions which exists, which has being, in all life, everywhere (in the Cosmos), simultaneously, and in the causal past, the present, and the future, of our world and of the Cosmos itself. For the acausal has no finite, causal, separation of individual, distinct, beings, and no linear casual-only progression of those beings from a past, to a present, and thence to some future. Rather, there is only an undivided life – acausal being – manifest, or presenced, in certain causal beings (living beings) and which presencing of acausality in the causal lasts for a specific duration of linear causal Time (as observed from the causal) and is then returned to the acausal to become presenced again in the causal in some other causal being in what, in terms of causality, is or could be the past, the present, or the future.

Therefore, for human beings, the true nature of being lies not in what we have come to understand as our finite, separate, self-contained, individual identity (our self) but rather in our relation to other living beings, human and otherwise, and thence to the acausal itself. In addition, one important expression of – a revealing of – the true acausal nature of being is the numinous: that which places us, as individuals, into a correct, respectful, perspective with other life (past, present and future) and which manifests to us aspects of the acausal; that is, what in former terms we might have apprehended, and felt, as the divine: as the timeless Unity, the source, behind and beyond our limited causal phenomenal world, beyond our own fragile microcosmic mortal existence, and which timeless Being we cannot control, manufacture, or imitate, but which is nevertheless manifest, presenced, in us because we have the gift of life.

David Myatt

2455347.197

Notes:

[1] These Aristotelian essentials are: (i) Reality (existence) exists independently of us and our consciousness, and thus independent of our senses; (ii) our limited understanding of this independent ‘external world’ depends for the most part upon our senses – that is, on what we can see, hear or touch; that is, on what we can observe or come to know via our senses; (iii) logical argument, or reason, is perhaps the most important means to knowledge and understanding of and about this ‘external world’; (iv) the cosmos (existence) is, of itself, a reasoned order subject to rational laws.

You must be logged in to post a comment.